Marge Tye Zuba

Born: in Chicago, Illinois

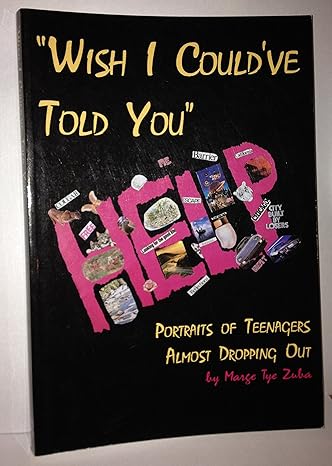

Pen Name: None Connection to Illinois: Zuba is a native Chicagoan. She is a member of the faculty at Northern Illinois University and has been on the faculty at the University of Illinois, DePaul, and Dominican Universities. Biography: Dr. Marge Tye Zuba is an internationally recognized educator, author, speaker and consultant on education, gangs, leadership, management and motivation. Utilizing her expertise in the area of Learning Styles, Motivation and Classroom Management, Marge has presented courses and workshops all over the world to educators, parents and businesses. She earned her doctorate in Leadership and Educational Policy Studies from Northern Illinois University and her Master's in Social World from the Jane Addams Graduate School of Social Work at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Marge has been a member of the faculty at Northern Illinois University where she spearheaded the first inner city graduate cohort program at Clemente High School in Chicago. She has also been on faculty at the University of Illinois, DePaul University and Dominican University. Currently Dr. Zuba is on faculty at Framingham State University International Educational Programs, DePaul University and Capella University. Dr. Zuba has spent more than twenty years as a high school teacher, creator and Director of a Chronic truancy Program, and Dean at Oak Park River Forest High School in Oak Park, Illinois. She has also worked with Latino street gangs in Chicago's Pilsen and Little Village area. Most recently, Dr. Zuba has worked with the Panamanian Ministry of Education in training ESL teachers throughout the country. Internationally, Marge has worked with teachers in Africa, Latin America, South America, Europe and the United States. She has authored "Wish I Could've Told You",a book chronicling the lives of students identified as Truants in a Chicago suburb. She also co-edited the book, Education/Change, which focuses on multicultural education.

Awards:

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/marge-zuba-18603064/

Web: http://www.margetyezuba.com

Selected Titles

|

Wish I Could've Told You: Portraits of Teenagers Almost Dropping Out ISBN: 1879528118 OCLC: 30914418 LEPS Press, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Ill. : 1995. |